The Scope Guys - Displacing Dumont and RCA

Early piece of electronic test equipment

Dumont Oscilloscope

For those of a certain age, or just those who have seen the reruns, you have seen a display of a very common piece of electronic test equipment, the show was the Outer Limits, and its open displayed an oscilloscope capturing the voice pattern of the narrator. An early Simpson's Halloween episode parodied this. An oscilloscope display has two axis. Horizontally represents time, and vertically the amplitude of the observed signal. There are many specialized versions of the oscilloscope, from waveform monitors that the television industry uses, automotive testers used to troubleshoot vehicles, to heart monitors used by the medical industry, to name a few. The traditional radar screen is a relative to the oscilloscope.

Modern iterations

To quote from Tektronix itself: "Tektronix oscilloscopes and related test and measurement equipment have been a cornerstone of the electronics industry for nearly three quarters of a century. Engineers use Tektronix products to advance the state of the art. The oscilloscope enables visualization and precise measurements of electronic devices, circuits, and systems."

A Braun Tube

The oscilloscope, or simply "scope" as it is used in the vernacular, developed around something referred to as the Braun tube, which came into being in the very late 1800s. The Braun tube evolved into the cathode ray tube (CRT). In 1899 Jonathan Zenneck equipped it with beam forming plates and a magnetic field for generating a sweep of the beam from left to right along the horizontal time axis, and a second set of plates to move the beam vertically as it swept horizontally.

By the early 1920s cathode ray tubes, the same type being developed for video, were applied experimentally to laboratory measurements. The problem at the time was that they suffered from not maintaining their internal vacuum for very long, along with the poor stability of the cathode, the element in the tube that emitted the electron beam. Zworykin started working on a permanently sealed, high vacuum cathode ray tube with a thermionic emitter in the early 30s. But it took Dr. Allen B. Dumont, who started a company in his basement in 1931 to make that happen.

1930s CRT

Dumont Laboratories improved the average CRT life from 24 hours to over a 1000 hours. This made television, and derivatives like the scope, possible. The company managed to beat RCA to market by almost a year with an all-electronic TV receiver in 1938. Besides TV, by the 1940s Dumont was a leader in the field of test equipment with their scopes. The problem was that the company did not have the resources to go head to head with RCA and others in both the fledgling broadcasting industry and the electronic test market. Its lead in scopes slowly slipped and in 1960 Fairchild Camera and Instruments bought what was left of Dumont after the Dumont TV Network, and the television equipment divisions had been closed down. The Dumont brand of scopes were sold until the 80s.

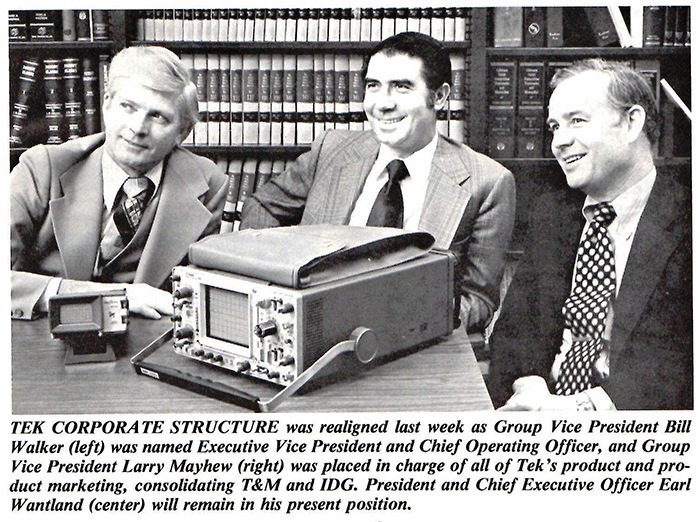

The eventual leader, both in sales and technology, in scopes was founded in 1945 near Portland, OR. The company was named Tektronix and was founded by four people. Charles Howard Vollum graduated from Portland Reed College with a degree in physics. Although small and far from the Ivy League, the school has had over a hundred Fulbright Scholars, 67 Watson fellows, and three Winston Scholar alumni. After graduation he operated a radio repair business in the back of an appliance store owned by another Tektronix founder, Melvin Jack Murdoch. During the war Vollum was involved with the radar signal corps. Murdoch during World War II worked in the Coast Guard as an electronic technician. The other two were Miles Tipperly, and Glenn Leland

Vollum was the president and Murdoch the vice president. The company started like another eventual large player in technology, Sony, which started about the same time an ocean away. Like the Sony founders, the Tektronix founders had no idea what they would sell, the four just wanted to manufacture, sell, and also repair electronic equipment. It was Vollum who decided that they would build an oscilloscope. It was designed using spare parts stockpiled by the partners during the war. The first one was as big as Vollum's workbench. Melvin brought in a Coast Guard machinist that he knew, to help reduce the size and this was completed in the spring of 46. It still weighed 50 pounds, but it functioned better than any other in existence. At the time Dumont was the largest producer of oscilloscopes. Vollum once said that all Dumont wanted to do was to fool round with big-time TV and they were complacent about their oscilloscope. By 1947 the company employed 12, and four years later had mushroomed to 250.

First Tektronix Scope

The first Tektronix oscilloscope, the company came to be known by customers as simply Tek, was the 511. In short time it was a success, bought by other major technology companies. By 1950 they had the 517, which was the seventh generation scope. In 1947 their sales were $27,000. The next year it shot to $250,000, and by 1950 it was over $1 million. At that time they had a backlog of orders almost a year long. Early customers were HP, Philco, RCA, Westinghouse, AT&T, and Bell labs. In 1948 they made their first overseas sale to L. M. Erickson which was a Swedish telephone company. By 1956 Tektronix was the scope king. A lot of their developments and inventions ended up in competitor's scopes, including the ones still offered by Dumont.

In the early 50s Murdoch started to lose interest in the company and took up flying, and even started an aircraft sales company on the side. At the companies beginning it was he who championed a "Tek" culture which centered on no perks for executives, and a family atmosphere with the use of first names, and that they should never have more than a few dozen employees. Although Tek paid lower wages, they offered better benefits and had profit-sharing. There were a few unbreakable rules. Employees were encouraged to follow their interests and at one time the company's culture was praised. The company took ideas from HP, whose founders Dave Packard and Bill Hewitt, developed what became known as "The HP Way." Similarly HP was a company that started with the goal of building electronic products, but "the question of what to manufacture was postponed." HP's original product was an audio oscillator, made much more stable by technical insights by the founders. An early customer was Disney, who used it in the making of the movie "Fantasia."

The HP startup case study, without revealing the company, in many MBA classes would be judged a formula for an abject failure. But in HP's case, it was not a product or its implementation that would turn into gold, it was the engineering culture they assembled from the beginning. HP encouraged its engineers to spend a part of their time on "skunk work" type activities that involved ideas that interested them. Often the founders would wonder the engineering caverns and stop by an engineer's workstation and bench, and look for some prototypical looking breadboard, box, or object and ask what that was about. The engineer would often attempt to convey how their developing idea would change the world or save mankind. Usually those efforts would not pan out, but once in every thousand or more stops, the idea for a new product would be hatched.

Vollum & Murdock

There is a strong compelling compulsion in engineering, as in other professions, that what I create might change the world. Even better if you work inside an organization that covers the overhead and keeps you fed and warm. Many companies over the years started and got large with this philosophic concept. HP, Sony, Xerox to name a few current survivors. The larger a company gets, the more hubris sets in, and meeting quarterly earnings grinds down the grand goal of bettering humanity. Tek at the beginning burrowed the same concept that HP managed to keep far longer than most. Murdoch was originally Tek's "HP Way" cheerleader.

Vollum was the driving force in the company when it came to basic engineering, and not the loftier philanthropic approach and outlook. He began the internal manufacturer of CRT's to get the quality that he wanted. He came up with plug-in modules for oscilloscopes in 1954, the model 530, which meant the scopes could be easily adapted for varied use. In 1955 one-half of all oscilloscope sales were the 530.

By the beginning of the 60s company sales were $43 million, and by the end of that decade the company had 75% of the oscilloscope market. Their total sales in 1969 was $148 million. When it came to scopes, they were beating HP by a large margin. HP at that time had a reputation for good, high end test equipment, that was slightly more designed in style and feel, and sometimes a little too much over-engineered. But Tek was the "working man's" provider of no-nonsense test equipment that got the job done at a price that management would pay. This was important because often, especially in the television industry, management wants to spend money only on what ends up affecting the product transmitted, and not the tools to maintain the technical integrity of the programing.

Soon the baggage that comes with getting large set in. In the early 60s Vollum convinced the Board of Directors to make Bob Davis the executive VP as Vollum was not equipped or inclined to give management the effort it needed. Davis had been in charge of manufacturing from 1954 to 1958 and he brought order to the operations. While reporting to Vollum, Davis ran the day to day operations. Davis was energetic and initially he was viewed as a positive step. But even by then there had developed an old guard that did not welcome change. They came to be known as the "old scope warriors." While there was significant growth under Davis and the companies first foreign subsidies started, the old guard prevailed. Already, the company was finding it difficult to branch into new areas of business. In 1962 Vollum was persuaded to retake control. A technology company that has problems innovating into new arenas often does not stay relevant for long. But Wall Street liked the outward buttoned down approach that Tek was following in the late 60s and it became an investors darling.

New campus

In the 60s the company built a new 300 acre complex in Beaverton, OR. In 1963 the company went public, and in the next year it was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Vollum told Forbes at the time that "there would always be an expanding need for scopes, because wherever electronics goes, the oscilloscope goes also." Over time though Wall Street changed its mind on the prospects of the company as it was not enamored with the fact that the company became so dependent on oscilloscopes. Computers were starting to be developed enough that they could mimic many of the testing duties that scopes did. More and more, not all electronics required access to an oscilloscope for design, testing, and troubleshooting. At this time, over 20 years after its founding, the company still did not have a lot of marketing experience since the oscilloscope up until then sold itself by being better and cheaper than the competition. Now the competition, even as the 60s ended, was coming from a new crop of companies, the computer manufactures.

Over the next few decades, more things electronic were at their heart, computers. More than one electronic entrepreneur became rich by finding a dumb electrical or electronic gadget and putting a microprocessor in it.

It is not that the company was not trying to branch out. In 1964 the company developed a way to keep an image on a CRT for up to 15 minutes. First used only on their test equipment, in 1969 they decided to sell these CRT terminals to other folks for other applications. Introduced in 1970 they were over engineered and costly. But with these terminals, for the first time since their original 511 scope the company was designing something for a competitive market. The company tried to diversify into programmable calculators but failed at that also. In 1971 earnings fell almost 35%. Employees took unpaid time off but not enough, and so the first layoffs occurred.

The company was facing additional headwinds. In 1971 Murdoch died when his seaplane flipped during takeoff on the Columbia River. While he was not involved with the day-to-day operations by then, he was still chairman of the board and was regarded as the person who gave the company their strategic vision. Another founder, Miles Tipperly, died about the same time.

Tektronix became a big player in television test equipment

Two common pieces of test equipment used in television

(Top) The waveform scope (video levels) (Bottom) The vector scope (color phase and saturation)

It ended up competing in adjacent markets to where the Group competed